Interview: Pacific Northwest pioneers dreamed of and perpetrated genocide, while historians covered it up

In his upcoming book, "The War on Illahee," historian Marc Carpenter documents the un-heroic genocidal invasions of settler militias that American historians later downplayed, omitted, or celebrated

When Marc James Carpenter began digging into United States pioneer history in the Pacific Northwest, he found many early territorial leaders who self-identified as “friends of the Indian” were hardly advocates for a shared humanity with Indigenous peoples—in fact, many called for their extermination by mass murder to take their lands.

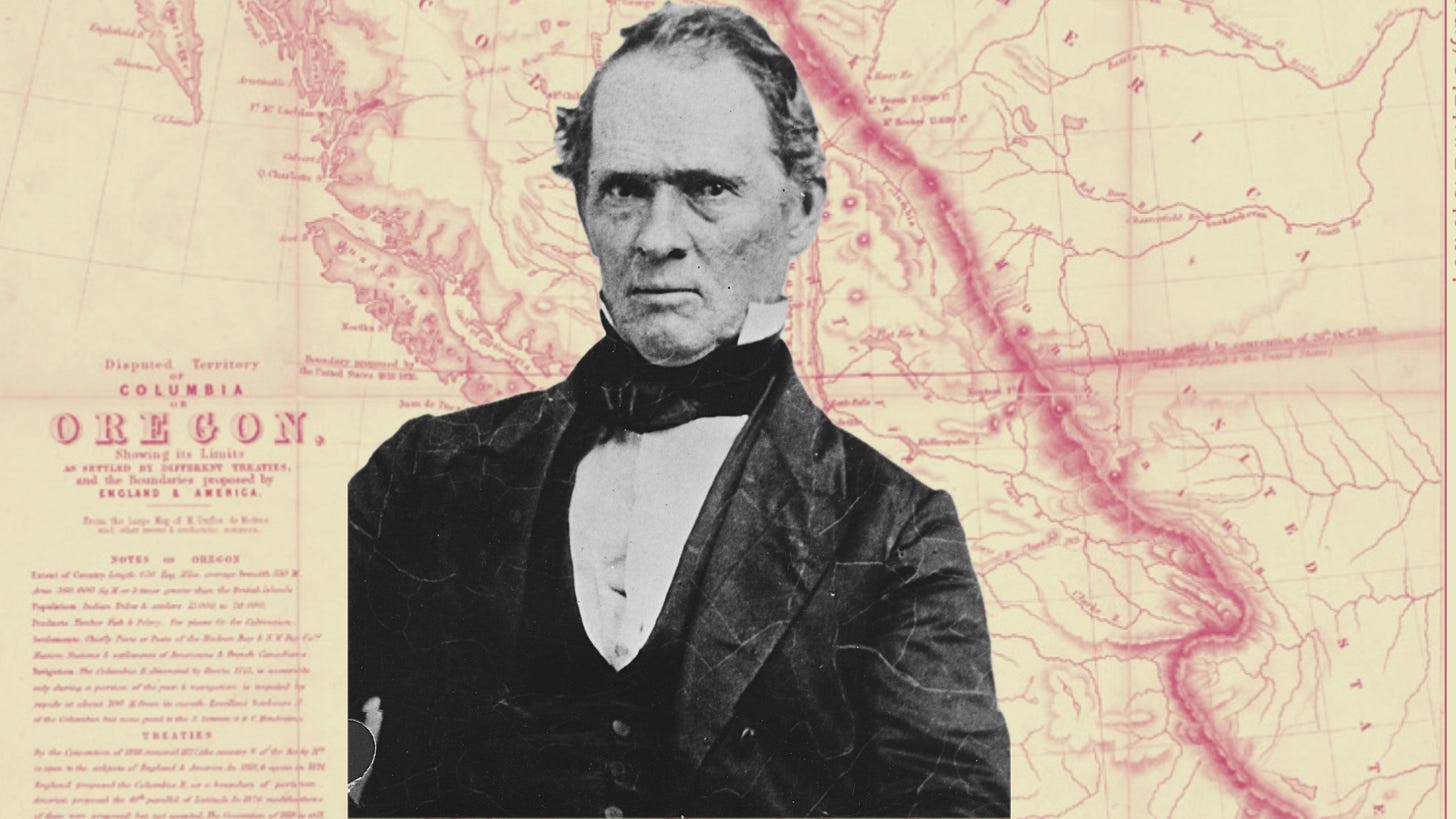

While addressing Congress, the longtime Indian killer and first territorial governor of the Oregon Territory, Joseph Lane, proclaimed that “the Injuns should be skulped [sic].”

Very few people in the mid-1800s, Carpenter found, took issue with annihilating Natives from the face of the earth. Many saw it as their destiny to “disappear.”

In his upcoming book, “The War on Illahee: Genocide, Complicity, and Cover-Ups in the Pioneer Northwest” (publishing Oct. 28), author and historian Marc James Carpenter has shed light on the depraved depths of America’s historical origins, the settler invasion into the Indigenous Pacific Northwest, and genocidal wars the early pioneers and modern historians tried to keep hidden.

The everyday violence of living in US-occupied Indigenous territories was ubiquitous and terrifying. For many tribes, giving up their lands through treaties was the only way to survive the ongoing siege of white settlers. “If you do not accept the terms offered and sign this paper,” a white negotiator recalled in June 1855, quoting the territorial governor who threatened Yakama leaders and held up the treaty, “you will walk in blood knee deep.”

A professor of American history at the University of Jamestown in North Dakota, Carpenter found that the continuous war and invasion against all Native peoples was consistently ignored or “prettied up” by the “Indian war veterans” and their regional historiographers. These historians had covered up decades of genocide, forced treaties, and land theft of the whole region through lies of omission, cleaning up US officials’ reputations, blaming Native tribes for “inciting” wars with settlers, and ultimately justifying the American invasion of Native lands. And Carpenter had the receipts.

While writing “The War on Illahee,” Carpenter let tens of thousands of pages of archival evidence speak for itself; that is, he let US officials and volunteer settler soldiers’ own words and actions shine through—often to a gruesome effect.

The bands of “volunteer” soldiers who roamed Indian territories regularly mutilated the bodies of Indigenous peoples they killed, often scalping their victims to collect a US bounty payout, and even mutilating various body parts as trophies to decorate their homesteads or even wear. In 1855, after committing a massacre of up to 75 Walla Walla/Walúulapam people, white men began stripping the tribe’s leader, Pio-pio-mox-mox, of his scalp and dividing up his body parts.

“Every man wanted a scalp of his head, there was not enough to go around so [doctor] Mack Shaw cut his ears off,” wrote one of the company’s volunteer soldiers.

“The War on Illahee” is a tale of white settler invasion, insatiable land hunger, sadistic bloodlust, and an unending string of genocidal massacres—and the historians and perpetrators who tried to cover it up. The story of America’s war on Illahee, Carpenter writes, begins with the so-called Cayuse War in 1847, a war that nationalist historians say began after Indians massacred whites at a mission, yet that is only part of the whole account.

And as Carpenter is adamant to express, this chronicle of the War on Illahee only scratches the surface.

“The War on Illahee: Genocide, Complicity, and Cover-Ups in the Pioneer Northwest” will be released on Oct. 28.

This interview is excerpted, lightly edited, and condensed for brevity and clarity by PBS standards.

Interview with Marc James Carpenter:

No Frontiers: I’m thrilled to get the chance to talk with you about your fantastic upcoming book. How did you come to research “The War on Illahee”?

Marc James Carpenter: I started to do some original research on a few major Oregonian figures who were supposedly Native rights advocates. I found some who were, right? Some who did talk to tribal peoples at a time when that was not normal. And I found some who claimed to be, quote unquote, “friends of the Indian,” but who were actually horrific people, who were murderers, who were rapists, who were in favor of genocide, and who nonetheless were remembered as quote unquote, “friends of the Indian.”

And it turned out it was a broader story. And the more I dug, the more I saw records that other historians had played a role in, kind of covering up the depth and the horror of those wars. I found that the wars didn’t really correspond to the frames that non-native historians had put on them.

It spiraled into this larger project. I realized that, according to both the Native people of Oregon and Washington in the 1850s and 1860s and to the American invaders, it essentially had been one long war.

What we’d remembered as a few individual wars that, frankly, we often don’t remember very well in American culture, things like the Cayuse War, the Yakima War, the Walla Walla War, to the people who were fighting and those who were defending in those wars. It was all the same war, right? It was the war for the land, the ‘war on Indians,’ as people put it.

And eventually, I decided to call the book “The War on Illahee,” a word for ‘homeland’ in the Chinook trade language, which was there before Europeans and then shared with them, a term most tribes would have recognized. And so it seemed like a useful name for a war for land that everybody involved would have recognized.

NF: Reading your book, it made me think a lot about broader American military history, or how military history was first conceptualized: It didn’t include these volunteer soldiers and irregular types of groups or armies, groups that maybe form to commit a “skirmish” or a massacre, but then disband because the war is over. They got their bounties or their pay. Could you elaborate on who the volunteer soldiers were who fought these “Indian wars” in the Pacific Northwest?

MJC: I think generally, military history, one of the places where it needs to go is taking more account of less regular troops, vigilante bands, right? of people who are not regulars in the US Army. And again, regulars in the US Army definitely took their share of horrors in this period. I don’t want to excuse them, but there’s also a broader American norm throughout most of the 1800s where it’s not unusual for a bunch of Americans to collect themselves together, call themselves volunteers, grab some weapons, and go shoot at people, usually native people.

This is an established norm in this period.

One of the points I try to make is that there is a transition from these self-declared volunteer soldiers in the 1850s gathering together, calling themselves a unit of the army, and killing people, and the lynch mobs that were much more common than is typically remembered in the same region in the 1870s and 1880s. Sometimes it’s the same guys doing that sort of thing. I worry about trying to parse how many people are volunteer soldiers, right? Most of the people whom we remember as volunteer soldiers, we remember that way because they successfully lobbied to get paid by the government for the violence that they did.

One of the illustrative and more famous matters that I write about essentially started with a local territorial government official, [James Lupton], getting down to the bar, telling everybody in town that he’d lied to the local native communities, [promising peace]. They’d be “off their guard,” he told them, and getting a bunch of guys with guns to go murder them. This is a bunch of murderers at a bar, but after the fact, they were declared volunteers by the government in some cases, because [Indian killing] is popular among a key part of their voters.

It’s harder to see that difference between how formal a soldier is in a period before you have kind of the more regimented, strict requirements for who is and isn’t a soldier. That’s more of a 1900s phenomenon.

NF: One of the themes that you talk about is that when history is written, there’s an emphasis on what the inciting incidents are to the “Indian wars.” What are the presented justifications for initiating a volunteer settler war on Native tribes or a village? And why do you feel there is too much emphasis by historians on these “inciting incidents” that start “Indian wars”?

MJC: So I think [when volunteer soldiers are talking] to the federal government, trying to get money in the 1850s and 1860s, or the kind of first generation of historians trying to pretty up the narrative—often the overwhelming focus when they’re trying to tell the story of a given war between Americans and a Native nation is to find an incident where Native people did violence to white people and call that the starting incident of the war, right?

A famous “inciting incident” for a war is the killing of adult men and a woman at the Whitman mission by a handful of Cayuse/Liksiyu warriors known as the Whitman Massacre, which is often cited as the beginning of the Cayuse War. There are also similar stories for the Yakama tribal killing of a federal agent named [Andrew] Bolon [in September 1855] as the supposed inciting incident of the Yakima War. And there are sort of two interventions I want to make in stories like that.

And I want to be clear, I’m not the only one who’s making this. I’m drawing from modern-day Native scholars. When I’m doing this, I don’t want to claim I’m the only one out here in this space.

One of them is to ensure we tell the story before that point. So in the case of the Yakima War, Bolon had been threatening to bring troops to murder everybody. He’d gone up there in the first place because the Yakima had executed a couple of trespassing would-be rapists, right?

In the case of the Cayuse, there seems to have been a trial where a Cayuse man found the Whitmans guilty of several capital crimes before attacking the Whitman mission. I think those stories are important. And I do dig into those. I think that even though sometimes we get too focused on the weeds and miss the bigger story, there are tens of thousands of Americans in this period who are pouring into the land and who are planning to kill Native people to take it, right?

And so, yes, we can trace the specifics of the conflict, right? We can trace wars to crimes the Whitmans were accused of, and whether or not they were guilty, but also, if none of that had happened, there still would have been “Indian wars.”

If there had not been the quote-unquote “Whitman massacre” or “Whitman incident”, there still would have been some war to take land from local Native communities. And we know that in part because the war was not fought solely against the Cayuse. It’s fought mostly against other local Native people whose land the pioneers wanted. And the pioneers themselves, at least in private, admitted that as much, right? They talked about the purpose [of the Cayuse war] as getting them off the land.

We need to disrupt narratives that falsely claim a start. Still, we also need to remember that at the end of the day, the core inciting incident is thousands upon thousands upon thousands of invaders who are coming into the land and are willing to kill to take it.

NF: When people look at history and are presented with settlers meeting with Natives, they will come upon the phrase “friend of the Indians”, but you pick that historical phrase apart. Can you describe what it actually means?

MJC: This phrase “friend of the Indian,” which again, if you’re in this historical space, you see this phrase all the time. I think many people, probably including me, have a sort of hunger for finding exceptions. Finding those pioneers—or to use my preferred phrase, “invaders”—in the period who are sympathetic to Native people and who have basic notions of shared humanity.

And there are a few, right? But I think in that hunger, people sometimes see that phrase “friend of the Indian” and take it to mean, “oh, good. This means this person is an ally,” and miss what they actually do.

So in the 1800s into the early 1900s, typically when somebody claimed to be a “friend of the Indian,” if they weren't lying, often what they meant was that Native people trusted me, right?

So I researched multiple people who identified as “friends of the Indian” who were supportive of genocide and took part in it, which is, I think we could all agree, an unfriendly act, right? And often the notion of “friend of the Indian” was projected onto them backwards, right? Either by themselves or by historians.

After fifty years, after the horrific violence of the War on Illahee, there was a notion that a “friend of the Indians” was one of the people who were friendly [to Natives], who knew the language, who was different from the people who came later. And so that got turned into “friend of the Indian”. But frequently that’s referring to something highly specific: It’s mostly a way of claiming you were there before other white people, or it’s a way of saying, “I knew their [Native] culture. I knew their language.” They usually didn’t, but it’s a way of claiming legitimacy.

[In documents] you’ll have people like Joseph Lane or Joseph Twogood who will say, ‘I was a friend of the Indian’ on one page and then on the next page, talk about how it was necessary to kill all of these Native people. And then their private writings are much, much worse, right? If you look at what they were writing privately in the 1850s, they’re fully in favor of mass killing and rape.

If somebody identifies as a friend of the Indian, that’s interesting and important, right? You do need to know that about them, but don’t assume that they’re telling the truth. And don’t assume that that means what we would think it means.

NF: In chapter four, you describe this kill/capture campaign. And just saying those two words, I think about how those campaigns are still waged by the US, right? Could you explain what exactly that campaign was, which you write was all over the Pacific Northwest Territory? Um, what? Yeah. What exactly was that campaign and why was it instituted?

MJC: So I don’t forget, I want to put in a minor plug for the book, “Indian Wars Everywhere,” which I think does a really great job connecting that. First of all, it was useful for me and did a great job connecting the shadow policies that were normal in the quote-unquote “Indian wars” in the 1800s, with some later US military policies from the 1900s to the 2000s.

When I talk about the War on Illahee, there’s sort of a point where it reaches a height in 1855-1856. It seems to have been a somewhat organized, but decentralized attempt to try and seize Native lands—I think they hoped all of the land in Oregon and Washington [Territories] by means of direct violence and by means of internment. It seems to have been this broad-based campaign again, uh, endorsed indirectly by the governors, uh, of those territories, uh, to send out volunteer troops and eventually to draw in what regular troops there were, uh, in, uh, suppressing Native peoples and trying to get them all pushed onto what we could call reservations. But again, seen in the period as prison camps, as internment camps, and attempting to get every [Native] into those, and everybody disarmed.

You see this in Oregon Territory, where there’s word from an official named Joel Palmer saying essentially, you know, ‘we are going to force all Native people into these camps. And if you see somebody not in the camps, you can take whatever steps you need to get them there.’

There was a similar move in Washington, and I’d say I’ve probably only scratched the surface of the stories of internment in either place, where there’s this attempt to move people onto the islands of the Puget Sound. There’s a mass attempt to disarm Natives.

And there’s good reason to believe that at least some of those attempts to disarm were intended as disarm and then exterminate, to kill, and to commit genocide.

I was particularly struck to find, in a relatively easy-to-find document, the initial plans for a genocide of the Chehalis people by the governor of Washington, which he decided not to go with because the disarmament efforts hadn’t been successful. And so the tribe would be able to fight back more than he was comfortable with.

On the ground, uh, this was often a military campaign of terror. So it would be the norm of a military, um, either responding to some supposed incident of violence of a Native against a white person, real or imagined, going into towns and demanding that people execute, right, as a means of attempting to establish violent supremacy. “Give us some murderers, or we will kill all of you, right?” And then trying to move from that to pushing Native people out to specific places. But they didn’t fully achieve their ends, right?

Today, many Native spaces are still in Native hands in the Pacific Northwest. Still, during this period, it was a genuine bottom-up attempt to constrain all Native people into prison camps and to reduce the number of Native people in those prison camps really rapidly. It’s not unreasonable to call that a genocide by the very technical legal definition of the term.

The US military’s a bit trickier because the federal push during that period was to keep costs down. So they thought that would be expensive and didn’t necessarily [monetarily] support it at the federal level, but at the local and state levels, the support was absolutely there.

I think one of the things I often notice that doesn’t appear in military histories, which tend to be top-down by just looking at the kind of orders from above, is the level of everyday violence from below, especially in these periods of heightened military action where I have people reminiscing the time they were young teenagers and recalling ‘oh yeah, during that time I saw a Native person and I shot him, and that’s when I became a man,’ right? These are major figures. That’s part of their reminiscence. That’s part of their self-identity.

One of the points I try to make is that we only have a narrow slice of the actual horror written down. We know it from Native communities that have oral histories and memories. Some of which are to be shared and some of which very much are not, right? There are stories that I couldn’t share in this book that aren’t for me. We know it from individual records. We know it from reminiscences. But we will probably never get to the full scope.

Any attempt at the number of deaths is going to be such a severe undercount that I didn’t attempt to count the number of deaths as a figure in the book because it would have been so radically below the actual breadth of the violence for Native land that was waged in the 1850s.

NF: We live in a fraught time for historical scholarship and a fraught time in general. How do you want people to connect with this book or understand this period in the Indigenous Pacific Northwest?

MJC: One of the things I’m really hoping is that we can move away from this valorization of the pioneer past. I think, specifically in the northwest and generally, we should recognize the horrific reality of it and try to build a better world than the one created by those pioneers, right? Move away from this valorization of one of the worst periods of the American past and build something new, build a world and a nation that is less involved in that kind of violence, one that perhaps moves towards justice.

I’d certainly say, if I’m dreaming, I would hope that this can play some small role in the longer-term truth, reconciliation, and reparations for the affected Native communities. At the very least, I hope that amplifying Indigenous voices, past and present, who have been frankly telling broader society this history since it happened, right? And that hasn’t always gotten through.

Part of the way that “The War on Illahee” is written and the way that I’ve underlined, again, evidence from perpetrators, the way that I draw on lots of indigenous evidence.

Overall, it’s both sides of the same story. There’s not really a debate among the people who were there about the broad shape of what happened. And I have a hope that proving the cover-up is part of how you get people to accept the crime.

I hope this isn’t just a book for people who are already ready to hear about it, though I hope it’s useful to those communities that are already well familiar with it. I hope it’s also a way of convincing a broader public that this happened in part by showing them what they don’t already know.

I think there is something useful in this regional lens, which demonstrates that this was planned, right? It was a somewhat coherent attempt to take Native land, not just by individual groups, and it weighs on the balance of evidence.

One of the stories that you see in a lot of Pacific Northwest history is when Native people are murdered by agents of the state or by volunteers because they were “killed while trying to escape.” And of course, you’ll see that in many other spaces, too, right? That’s kind of a classic thing of police, carceral violence, violence of the armed forces. And I think showing how often that was a somewhat deliberate lie. How often? Because I’ve got pioneers writing ‘Oh, yeah. We say that when we want to kill somebody,’ Right? ‘We said, oh, yeah, he died while trying to escape.’ And I think showing that can weigh on the evidence in individual cases.

When Indigenous communities are making the case that somebody from their community was actually murdered, who was not killed while trying to escape, the fact that we have evidence that people all over the region were actually murdered will help weigh on the balance of the evidence, even when we don’t have a specific pioneer saying that, ‘yeah, we were lying,’ right? Once you highlight a particular norm of pioneer lies, it allows you to reconfigure how you think about that history and recognize how often pioneer lies are part of the story. [*]

UPDATE: An earlier version of the story had a photo caption claiming Joseph Lane campaigned to be the first territorial governor of the Oregon Territory when he was actually appointed to this position, and later campaigned to be a territorial delegate in the 1950s. No Frontiers regrets this error.

Title: The War on Illahee: Genocide, Complicity, and Cover-Ups in the Pioneer Northwest | Author: Marc James Carpenter | Price: $38 USD | ISBN: 978-0-300-27573-5 Hardcover *eBook ISBN: 978-0-300-28576-5 | Pages: 400 | Yale University Press, publication date: 28 October 2025

You can also read Carpenter’s essay “They Bloody Origins of the Word ‘Pioneer’” here.

https://soundcloud.com/antithesis-crew/intro-genocide-featuring?in=antithesis-crew%2Fsets%2Fthe-power-of-purpose

Living in the PNW now, I'll look forward to this book. I recently wrote about the role of pioneers/volunteer militias in Native genocide. They played huge roles across the country, and were often responsible for massacres of peaceful encampments: Sand Creek and Camp Grant come to mind. Throughout the 1700s and 1800s, it feels like every able-bodied white male pioneer was essentially a volunteer soldier, and a bit out of control at that.

During the Cherokee Trail of Tears, they made up the majority of General Winfield Scott's "army." See my recent post: https://substack.com/@schampton/p-175629097.

These same volunteers had acquired rights (via a Georgia lottery) to Cherokee lands and thus had designs on specific parcels. Two of Scott's underling generals were so repulsed that they quit, but before they did, they sought to use regular enlisted men to protect the Cherokees from the volunteer militia. One of these, General Wool, ended up in the PNW and acted similarly there. I'm sure he's covered in Carpenter's book, as he had a lot to say about crazed white pioneer militias. My post mentions Joel Palmer as well, who worked with Wool until he was fired.

In Washington, Oregon, and especially in California, the federal military sometimes put Natives into stockades specifically to protect them from marauding pioneers bent on "extermination" - a very common word in the historical record during the mid-1800s, often uttered by politicians in favor of it. The problem of violent pioneers was so pervasive that, during the national debate over the Indian Removal Act (1830), many white liberals supported this mass ethnic cleansing (moving all Natives west of the Mississippi) as a way to save them from genocide.

And there's a common pattern after the massacres. There's an investigation in DC. The volunteer militias are condemned but excused (the term "regrettable events" is common), and almost never punished. In many instances, the militias were led by someone prominent who now has a town or county or mountain named after them.